|

enginehistory.org

Aircraft Engine Historical Society Members' Bulletin Board

|

| View previous topic :: View next topic |

| Author |

Message |

mroots

Joined: 20 Nov 2014

Posts: 4

|

Posted: Sat Oct 24, 2015 14:29 Post subject: Why have bores of 6.125" Posted: Sat Oct 24, 2015 14:29 Post subject: Why have bores of 6.125" |

|

|

| I read somewhere that just over 6.125" is about the best bore size. Can anyone explain the theory behind establishing this please? Thanks, Marc |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

kmccutcheon

Joined: 13 Jul 2003

Posts: 299

Location: Huntsville, Alabama USA

|

Posted: Sun Oct 25, 2015 13:10 Post subject: Posted: Sun Oct 25, 2015 13:10 Post subject: |

|

|

There are at least two aspects to this --- an engineering one and a historical one.

Engineering

All engine designs are collections of compromises. High-performance aircraft engines have evolved to a combination of bore, stroke, cylinder number, and rpm that provide the maximum specific power, while still preserving reliability and good fuel economy. It turns out that bores larger than about 6.125" are too large for the two combustion flame fronts, which optimally start at opposite sides of the cylinder, to traverse the cylinder during the time the piston is close to top center and able to absorb the energy liberated. In addition, large cylinders are a bit more prone to detonate and are harder to cool since the have longer heat paths for the valve seats, valve guides, cylinder head and piston crown.

Historical

All U.S. aircraft engines with bores greater than 5.500" were built by Pratt & Whitney or Wright, but the story starts with Charles Lawrance, who began developing air-cooled radial engines just after WW1. Although Wright tried to build air-cooled radials of its own, none were successful. The U.S. Navy essentially forced Wright to acquire Lawrance's company in 1923, and the engines that resulted were named Whirlwinds.

Frederick Rentschler was President of Wright at the time, but resigned in 1924 because the money-grubbing investment bankers that owned the company would not allocate sufficient money for research and development. Rentschler formed Pratt & Whitney Aircraft in 1925 and promptly raided the Wright brain trust.

P&W ran its first Wasp (R-1340) on 28 Dec 1925 and delivered its first production engine on 4 Aug 1926, 219 days later. The Wasp, with a bore of 5.750", had a takeoff rating of 410 hp at 1,900 rpm.

Even before the first Wasp was running, P&W began work on a larger engine, the Hornet A (R-1690), with a bore of 6.125". This engine first ran on 16 Jun 1926 and the first one was delivered 24 Mar 1927, 281 days later. The Hornet A initially had a takeoff rating of 525 hp at 1,900 rpm, but was refined (Hornet C, D and E) and produced through 1942, with an eventual takeoff rating of 875 hp at 2,300 rpm.

In the mean time, Wright raided the U.S. Army Air Corps Power Plant Division brain trust and introduced the R-1750 Cyclone with a 6.000" bore in late 1927. It had a takeoff rating of 552 hp at 1,900 rpm.

Not to be outdone, P&W countered with the Hornet B (R-1860), with a 6.250" bore and a takeoff rating of 575 hp at 1,950 rpm. However, the Hornet B was problematical. It first ran on 7 Nov 1927, but the first one was not delivered until 27 Jun 1929, 598 days later! This long period suggests development difficulties, and it also had a poor service reputation, perhaps a result of detonation in the big cylinders running on the 73 octane fuel available at the time. The engine never achieved more than 650 hp at 2,000 rpm. P&W only built 446 Hornet Bs between 1929 and 1934.

Wright countered the Hornet B with the R-1820 Cyclone in Jul 1930. The R-1820 had a bore of 6.125" and a takeoff rating of 575 hp at 1,900 rpm. However, this engine was eventually developed to the point that it produced 1,675 hp at 2,800 rpm.

Meanwhile, P&W had built its first experimental two-row air-cooled engine, the R-2270. The success of this endeavor led to the first Twin Wasp, with 14 cylinders and a bore of 5.500". This engine first ran on 16 Apr 1931, and remains the most produced aircraft engine ever. When the time came to build an even larger engine, P&W chose a cylinder with a 5.750" bore and a 6.000" stroke. Eighteen of these comprised the R-2800. Cylinders of identical bores and strokes comprised the R-2180 and R-4360.

_________________

Kimble D. McCutcheon |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

mroots

Joined: 20 Nov 2014

Posts: 4

|

Posted: Wed Nov 04, 2015 13:05 Post subject: Posted: Wed Nov 04, 2015 13:05 Post subject: |

|

|

| Nice answer Kimble, Thankyou. |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

wallan

Joined: 13 Jul 2003

Posts: 252

Location: UK

|

Posted: Thu Nov 05, 2015 04:51 Post subject: Posted: Thu Nov 05, 2015 04:51 Post subject: |

|

|

I once asked a lecturer at university why the twin flame fronts in an aero-engine didn’t detonate the rest of the mixture as they approached each other, and cause detonation/pinking. He suggested that could be my PhD project! I was too busy reading books to bother about that.

I have a book, originally written in German, called something like, “Engineering Design, blah, blah, blah”. It has an orange cover and is about how best to design (economically) for manufacturing single or multiple items. (casting, machining, welding, etc.) I have no idea where it is. The author obviously comes from a marine engineering background, and states that when internal combustion engines are constructed with cylinders much above six inches bore and stroke, the scantlings, (the bits that make up the engine) become affected under the cube rule, whereby the weight of the engine becomes increasingly heavier, (twice as big, eight times heavier) causing the power to weight ratio to rapidly decrease. |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

kmccutcheon

Joined: 13 Jul 2003

Posts: 299

Location: Huntsville, Alabama USA

|

Posted: Thu Nov 05, 2015 06:43 Post subject: Posted: Thu Nov 05, 2015 06:43 Post subject: |

|

|

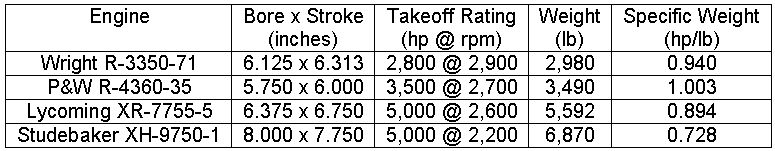

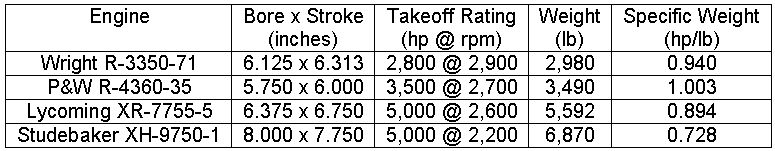

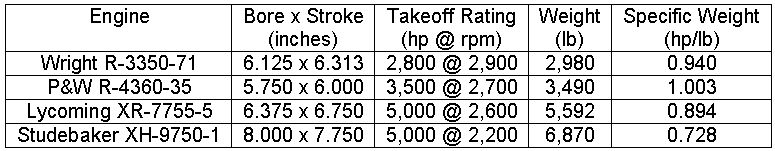

I think the square/cube idea is borne out with a comparison of large US engines using data from Model Designations of U.S.A.F. Aircraft Engines. This data all comes from the same period.

One should note that both the Lycoming and Studebaker required exhaust turbosuperchargers to produce these ratings and were liquid cooled. The additional (substantial) weight of the turbochargers and cooling systems is not included. Even thought the comparison is biased toward the big engines, one can see their specific weights are worsening.

At the time these really big engines were conceived, Air Force doctrine was aimed at very large, very long range bombers using engines with extremely good fuel economy. For long missions, the extra weight of the engines was offset by the reduced fuel requirements, resulting in powerplant plus fuel weights that were lower than with smaller engines. This was discussed in detail during George Cully's presentation at the 2012 AEHS Convention.

_________________

Kimble D. McCutcheon |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

sdavies

Joined: 14 Jul 2019

Posts: 2

|

Posted: Wed Jul 17, 2019 13:23 Post subject: Posted: Wed Jul 17, 2019 13:23 Post subject: |

|

|

| kmccutcheon wrote: | I think the square/cube idea is borne out with a comparison of large US engines using data from Model Designations of U.S.A.F. Aircraft Engines. This data all comes from the same period.

One should note that both the Lycoming and Studebaker required exhaust turbosuperchargers to produce these ratings and were liquid cooled. The additional (substantial) weight of the turbochargers and cooling systems is not included. |

The details of mechanics would in some cases differ with this statement. The much larger weight of the larger pistons/cylinders, air cooling fins, heavier head forgings and other stuff out weigh the much lighter water jackets, plumbing and radiators.

Point in case the R-2800 could be had at a power rating of 2200 HP, while a contemporary Packard-Merlin made 2218 HP from less weight for the same TBO. While later R-2800s could make more power if turbocharged, they were shorter lived and still heavier per HP than the Merlin, plus all of it's accoutrements and it was not as good as the V-1710, all things considered. |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

rwahlgren

Joined: 15 Aug 2003

Posts: 324

|

Posted: Mon Nov 25, 2019 22:07 Post subject: Posted: Mon Nov 25, 2019 22:07 Post subject: |

|

|

I think TBO for 2800's ended up in the 3,000 plus range. Inlines are

more in the 600 or so range. The radial engine has a much stronger crankcase than an inline, and fewer main bearings, and shorter crankshaft.

Thus more capable of higher power ratings than the cast aluminum crankcase of an inline. I thought I had read that for racing, strengthening plates needed to be added to the crankcases of inlines that are operated at high boost power settings, for engines used in race planes and hydro planes, I suppose any tractor pullers do the same.

(edit 12/1319)

If there was any advantage, to inlines they would have been the popular choice in the time after ww2 until the jets arrived. As mentioned above

the TBO's of the inlines never was as high as the aircooled radial engines.

Go to this website, which says they like to see an engine back at around 500 to 600 hours for the next overhaul.

https://www.vintagev12s.com

The merlins are well known for a few parts that wear prematurely.

In the early 1950's, airlines were overhauling R-2800's at 1200 hours.

In the years since that, TBO has almost doubled. |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

|

Powered by phpBB © 2001, 2005 phpBB Group

|